HISTORIC MARKER

Fort Buenaventura

41° 12′ 53.3″ N • 111° 59′ 23.8″ W

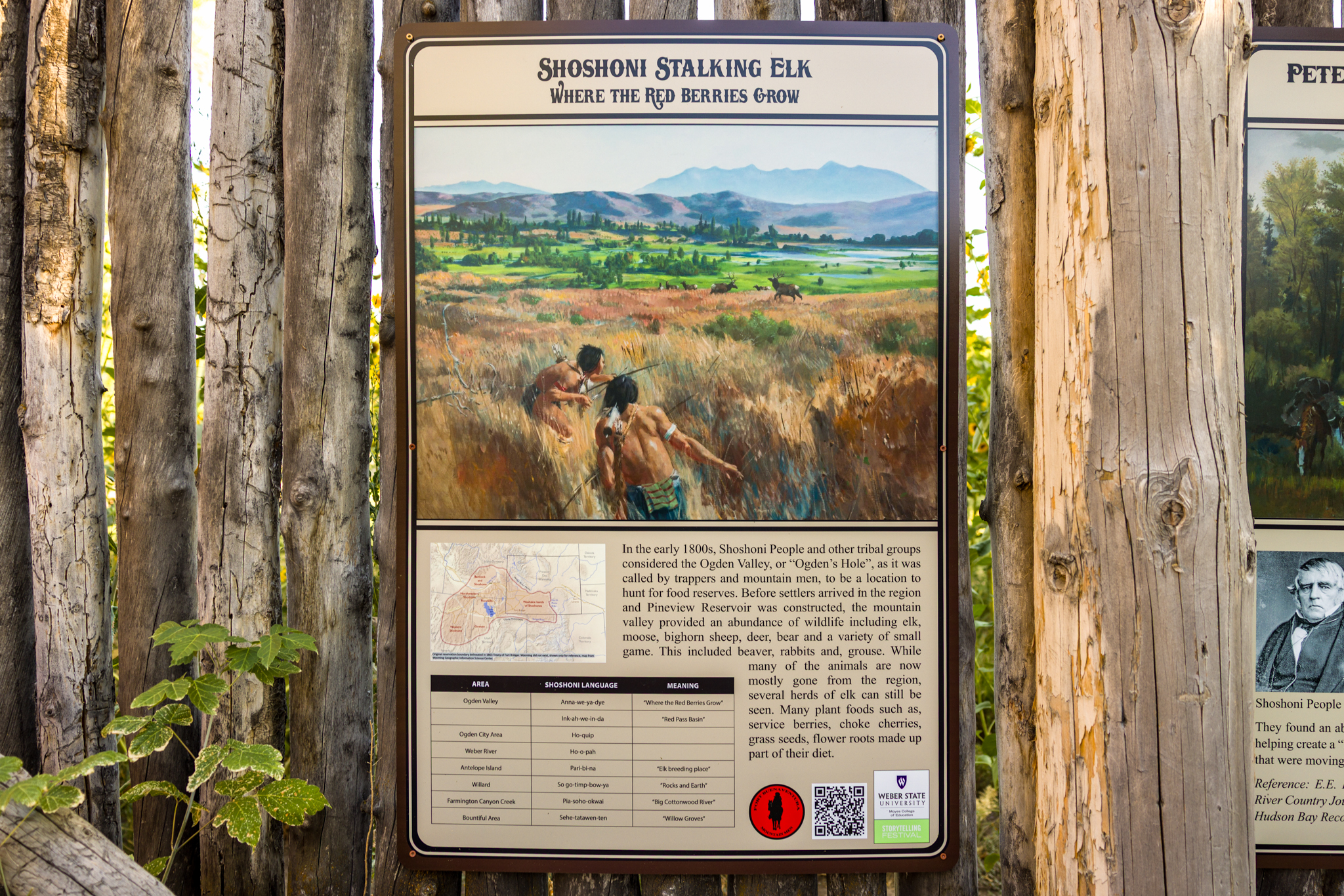

Before the fur trade era, which began significantly impacting the Intermountain West around the early 19th century, the Shoshone people thrived across a vast region encompassing parts of present-day Idaho, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, and Montana. This area, characterized by diverse landscapes including the Great Basin, Snake River Plain, and mountainous terrains, shaped a resilient and adaptive Native American lifestyle. The Shoshone, divided into subgroups such as the Eastern, Western, and Northern Shoshone, maintained a rich cultural and economic existence rooted in their environment, predating European influence.

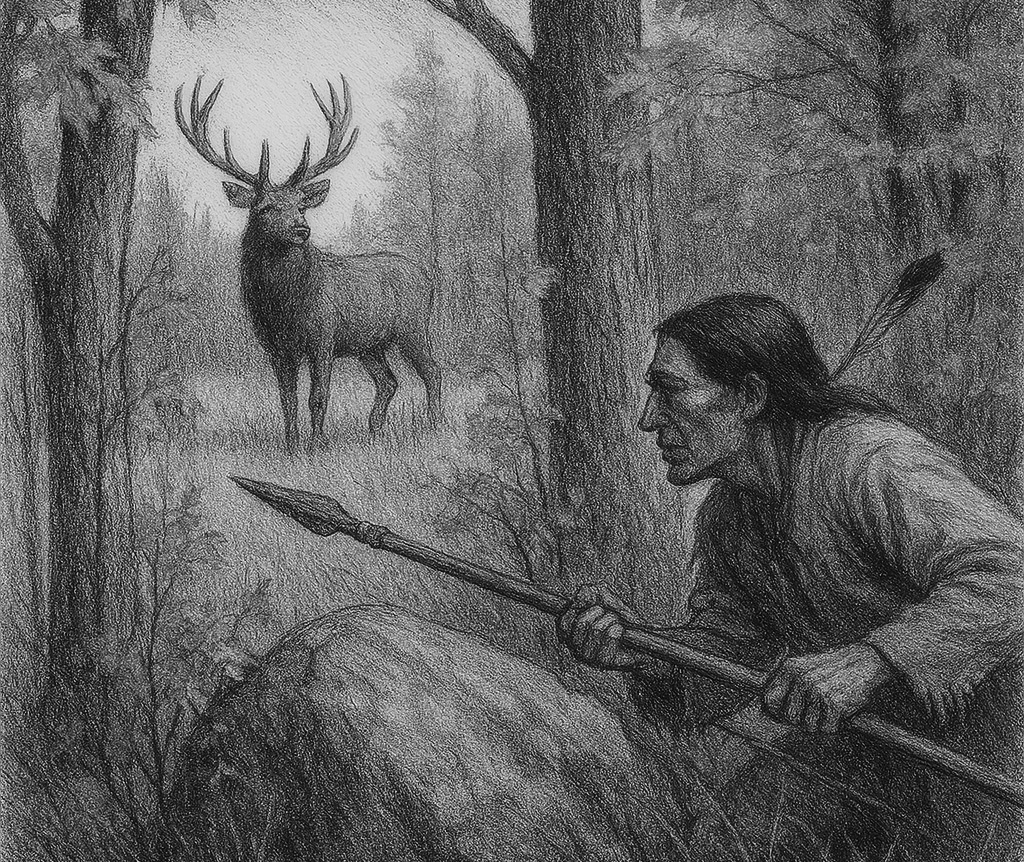

The Shoshone were primarily hunter-gatherers, relying on the region’s abundant natural resources. The Eastern Shoshone, inhabiting the plains and foothills, excelled in bison hunting, using sophisticated techniques like communal drives into corrals or over cliffs, a practice noted in oral traditions and archaeological evidence. They crafted tools from bone and stone, including bows and arrows, and processed hides for clothing, tipis, and storage. In contrast, the Western and Northern Shoshone, adapted to the Great Basin’s arid conditions, focused on small game like rabbits and pronghorn, often employing nets or communal hunts. Seasonal migration was central, with groups moving to higher elevations in summer for roots, berries, and seeds—such as camas and biscuitroot—and returning to sheltered valleys in winter for cached food stores.

Social organization was flexible, typically organized into small, family-based bands led by knowledgeable elders or skilled hunters. These bands, numbering 10-50 individuals, fostered cooperation for survival, sharing resources during scarcity. Marriage alliances strengthened ties between bands, while oral traditions, songs, and dances preserved their history and spirituality, centered on reverence for nature and spirits like the Creator or Wolf, as reflected in their narratives. Shelter varied by region: the Eastern Shoshone used portable tipis, while Western groups constructed wickiups from willow branches, suited to their semi-nomadic life.

resources during scarcity. Marriage alliances strengthened ties between bands, while oral traditions, songs, and dances preserved their history and spirituality, centered on reverence for nature and spirits like the Creator or Wolf, as reflected in their narratives. Shelter varied by region: the Eastern Shoshone used portable tipis, while Western groups constructed wickiups from willow branches, suited to their semi-nomadic life.

Trade existed pre-fur trade, though on a smaller scale, with the Shoshone exchanging obsidian, shells, and basketry with neighboring tribes like the Ute and Paiute. Their diet was diverse, supplemented by fishing in rivers like the Bear and Snake, where they used woven traps, and gathering pine nuts and wild onions. This subsistence strategy ensured resilience against environmental fluctuations, with evidence from archaeological sites like those near Bear Lake showing long-term habitation patterns.

The arrival of horses, possibly by the 1700s via southern tribes, revolutionized Shoshone life, particularly for the Eastern bands. Horses enhanced hunting efficiency and mobility, enabling trade expansion and occasional warfare, though the Intermountain Shoshone remained less militarized than Plains tribes. Spiritual practices, including vision quests and healing ceremonies, reinforced community cohesion, with shamans playing key roles.

This pre-fur trade era ended with Euro-American exploration in the early 1800s, as the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-1806) and subsequent fur traders disrupted traditional patterns. The Shoshone’s self-sufficient life, adapted to the Intermountain West’s challenges, was soon challenged by disease, displacement, and competition, setting the stage for the dramatic changes documented in events like the Bear River Massacre of 1863. Their pre-contact legacy, however, underscores a sophisticated adaptation to a harsh yet bountiful landscape.