HISTORIC MARKER

Fort Buenaventura

41° 12′ 53.3″ N • 111° 59′ 23.8″ W

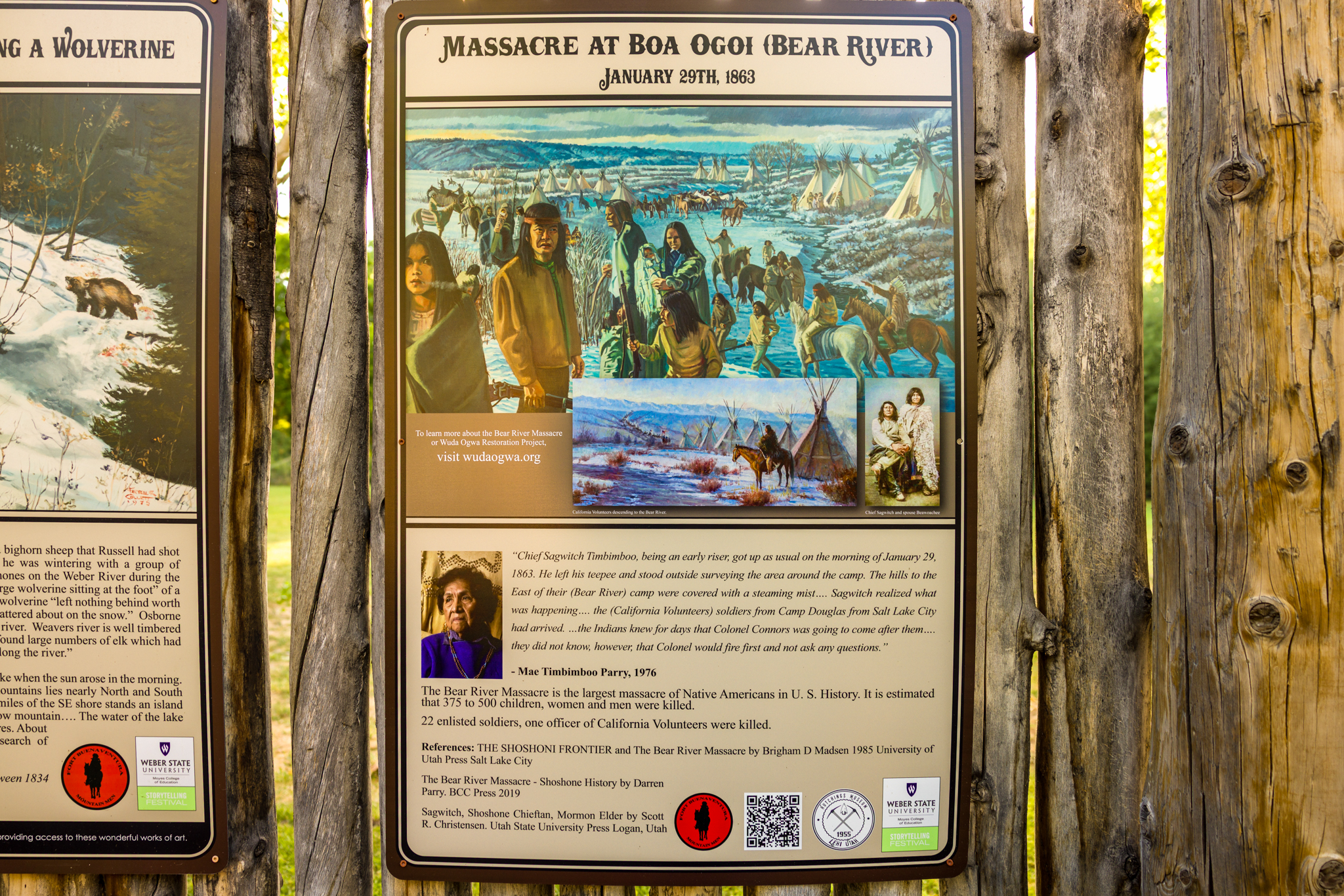

The Bear River Massacre, also known as the Massacre at Boa Ogoi, occurred on January 29, 1863, near present-day Preston, Idaho, marking one of the deadliest attacks on Native Americans by U.S. forces in history. The event targeted a winter encampment of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone, a group whose traditional homeland, Cache Valley—known to them as Boa Ogoi or “Willow Valley”—had been increasingly encroached upon by white settlers. Estimated casualties range from 250 to 493 Shoshone, including men, women, and children, with 21 U.S. soldiers killed and 46 wounded, reflecting a disproportionate and brutal assault.

The Bear River Massacre, also known as the Massacre at Boa Ogoi, occurred on January 29, 1863, near present-day Preston, Idaho, marking one of the deadliest attacks on Native Americans by U.S. forces in history. The event targeted a winter encampment of the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone, a group whose traditional homeland, Cache Valley—known to them as Boa Ogoi or “Willow Valley”—had been increasingly encroached upon by white settlers. Estimated casualties range from 250 to 493 Shoshone, including men, women, and children, with 21 U.S. soldiers killed and 46 wounded, reflecting a disproportionate and brutal assault.

The massacre’s roots lie in the mid-19th century, as the California and Oregon Trails, along with Mormon settlement in Utah starting in 1847, disrupted Shoshone life. The influx of settlers depleted game and resources, pushing the Shoshone into starvation and desperation, leading to retaliatory raids on farms and ranches. Tensions escalated with incidents like the 1860 killing of a Shoshone youth accused of horse theft and the 1859 Fort Hall massacre, fueling settler demands for military action. In response, Colonel Patrick Edward Connor led approximately 200 California Volunteers from Camp Douglas, Utah, on a winter expedition to suppress the Shoshone, targeting Chief Bear Hunter’s camp at the confluence of the Bear River and Battle Creek.

On that frigid morning, Connor’s troops launched a surprise attack as Chief Sagwitch noticed an approaching fog, later revealed as soldiers’ breath in the subzero cold. The Shoshone, caught off guard, mounted a desperate defense from a ravine, but the soldiers’ superior firepower overwhelmed them. Eyewitness accounts describe horrific scenes:  some Shoshone fled into the icy river, only to be shot, leaving it “brimming with dead bodies and blood-red ice.” Soldiers reportedly committed atrocities, including killing unarmed women and children, with estimates suggesting up to 400 deaths. The camp’s 75 lodges and food stores were destroyed, exacerbating the survivors’ plight.

some Shoshone fled into the icy river, only to be shot, leaving it “brimming with dead bodies and blood-red ice.” Soldiers reportedly committed atrocities, including killing unarmed women and children, with estimates suggesting up to 400 deaths. The camp’s 75 lodges and food stores were destroyed, exacerbating the survivors’ plight.

The U.S. Army framed the event as the “Battle of Bear River,” a victory in the context of the Civil War-era Indian Wars, but Shoshone oral histories and modern scholarship recognize it as a massacre. The attack’s scale surpassed later events like Wounded Knee, yet it received scant attention due to the Civil War’s dominance in national focus. Survivors, led by Chief Sagwitch, fled to Franklin, Idaho, struggling to rebuild amid trauma.

Today, the site remains sacred to the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone, who purchased it in 2008 and expanded holdings in 2018 to create the Boa Ogoi Cultural and Interpretive Center. Efforts include ecological restoration, guided by ethnobotanical records from Mae Timbimboo Parry, to revive native plants like willows and honor the land’s cultural significance. The massacre’s legacy is one of resilience, as the Shoshone work to reclaim and heal Boa Ogoi, a testament to their enduring spirit despite a cataclysmic loss that forever altered their community.

Sources

- THE SHOSHONI FRONTIER and The Bear River Massacre by Brigham D Madsen 1985 University of Utah Press Salt Lake City

- The Bear River Massacre – Shoshone History by Darren Parry, BCC Publishing

- Sagwitch – Shoshone Chief, Mormon Elder by Scott R. Christensen, Utah State University Press Logan, Utah

(Click images below for larger view)

Historic Marker