Bamberger Railroad

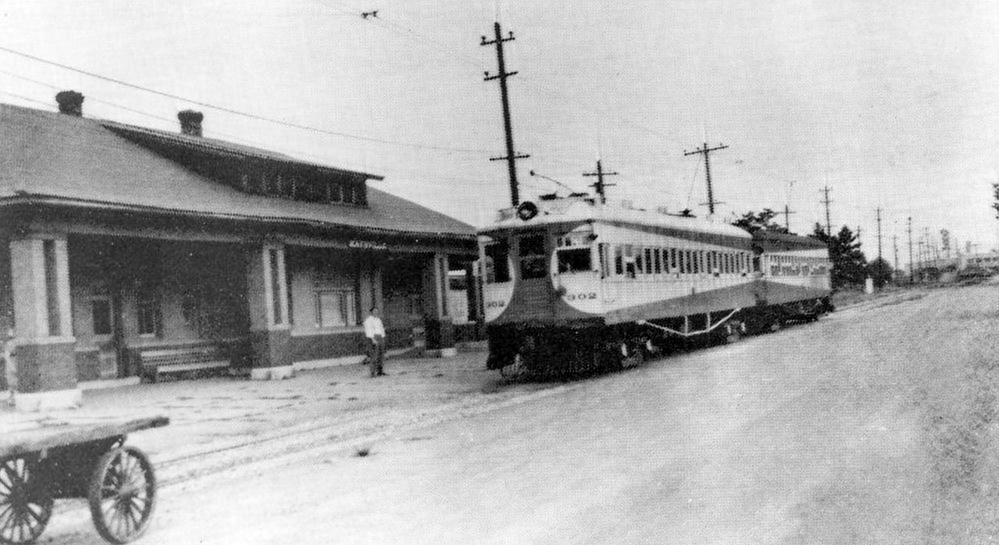

The depot was located on the west side of 100 east, directly across from Kaysville Elementery.

Simon Bamberger According to the UtahRails.net website, the Bamberger Railroad got its start in 1891 as the Great Salt Lake & Hot Springs Railway, when Utah mining millionaire, Simon Bamberger (1845-1926) believed a local railroad that would serve the farming communities between Salt Lake and Ogden would be a profitable venture. The first goal was to build a four mile rail line to connect downtown Salt Lake City to Beck’s Hot Springs, a popular hot water resort since pioneer times, near the Salt Lake/Davis county line.

According to the UtahRails.net website, the Bamberger Railroad got its start in 1891 as the Great Salt Lake & Hot Springs Railway, when Utah mining millionaire, Simon Bamberger (1845-1926) believed a local railroad that would serve the farming communities between Salt Lake and Ogden would be a profitable venture. The first goal was to build a four mile rail line to connect downtown Salt Lake City to Beck’s Hot Springs, a popular hot water resort since pioneer times, near the Salt Lake/Davis county line.

The first trains to this resort were duplicates of the trains that operated on the elevated railroads of Brooklyn New York. Power for the first trains was ‘steam dummy’ locomotives, small steam locomotives with a car body over the mechanism to resemble a trolley car.

The company completed its line to Beck’s Hot Springs later in 1891, and continued on to Bountiful in less than a year. Centerville was reached in 1894, and Farmington in 1895. About that time, Bamberger, who was vice president and co-owner of a resort called Lake Park on the shores of the Great Salt Lake that would close in 1895 due to the lake’s receding, bought most of the original resort buildings from the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad and moved them three miles east to a swampy area in Farmington that he drained. There, he built the Lagoon Resort, which attracted riders from both Salt Lake and Ogden as well as the many towns in between.

The company was reorganized in October 1896 as the Salt Lake & Ogden Railway. The end of track remained at Lagoon from 1896 through 1902. Bamberger then resumed construction, continuing to expand his rails north, reaching Kaysville and Layton in 1906 and eventually Ogden in 1908. Passenger Service between Salt Lake City and Ogden began on August 8, 1908.

On May 28, 1910 the Salt Lake and Ogden Railway became electrified, meaning it was run by huge electric motors. The motto became “On the hour every hour.” This meant a train left Salt Lake City and Ogden each hour during the day, stopping at each city and passed each other at Kaysville, each arriving at their destination in time to make a new run on the hour. This was remarkable when it took a horse and buggy a full day to travel the same distance of 40 miles.

Though it was still the Salt Lake & Ogden Railway officially, it was locally called “the Bamberger,” and in August 1917, the name was changed officially to the Bamberger Electric Railroad. That was also the year Simon Bamberger was elected Utah’s fourth governor as the Progressive Party candidate.

Bamberger passenger and freight trains had been providing interurban railroad services to Kaysville citizens for fifteen years but during that time the city didn’t have an official depot. There were many reasons for the depot construction delay. However, when it did happen there was a citywide celebration in Kaysville.

Under the headline “WE HAVE THAT DEPOT,” a reporter wrote a story covering the dedication in The Weekly Reflex on February 3, 1921. “Kaysville has her new Bamberger Electric Railway depot and it is some depot,” the article said. “As a matter of fact, it is the finest and most commodious depot on the interurban system outside of Salt Lake City and Ogden. The building is of concrete, pressed brick, and steel and is the last word in interurban depot construction.”

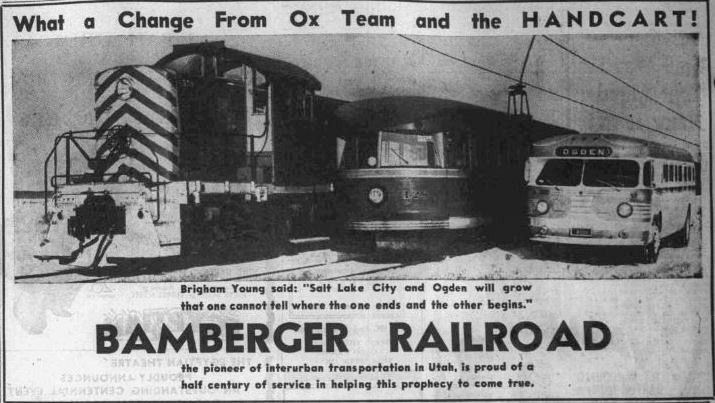

Due to declining business, Bamberger Electric Railroad declared bankruptcy in 1933, emerging in 1939 as the reorganized Bamberger Railroad, dropping the word “Electric” from its name.

Things Changed Over The Next 10-15 years

The Bamberger railway survived World War II, because of a great demand for transporting goods and people. Gas rationing was prevalent and people working at Hill Field and the Naval Supply Depot needed transportation. Soon after the war its popularity began to diminish. Automobiles, trucks and buses took over. By the early 1950s, the company was struggling to make ends meet, even as it tried switching its passenger business from rail cars to buses.

In talking about the reasons for the rail line’s demise, Julian Bamberger, Simon’s son and the Bamberger president, was quoted as saying: “We hate to see this day, but it had to come. The disastrous fire last April destroyed our repair shops and service equipment. And, it seems we’re in a collision with the automobile as everyone wants to drive their car now so we have decided to switch over to highway bus operations. We will continue to serve commuters along the Salt Lake-Ogden route with buses while freight service will be handled by recently acquired diesel locomotives. Unfortunately, no one wants to ride a train anymore.”

The Bamberger ended its passenger train operations Sep. 6, 1952, and freight service ceased operations Dec. 31 1958. Much of the Bamberger right-of-way was eventually purchased by the federal government for the I-15 freeway.

According to the UtahRails.net website, the Bamberger Railroad got its start in 1891 as the Great Salt Lake & Hot Springs Railway, when Utah mining millionaire, Simon Bamberger (1845-1926) believed a local railroad that would serve the farming communities between Salt Lake and Ogden would be a profitable venture. The first goal was to build a four mile rail line to connect downtown Salt Lake City to Beck’s Hot Springs, a popular hot water resort since pioneer times, near the Salt Lake/Davis county line.

The first trains to this resort were duplicates of the trains that operated on the elevated railroads of Brooklyn New York. Power for the first trains was ‘steam dummy’ locomotives, small steam locomotives with a car body over the mechanism to resemble a trolley car.

The company completed its line to Beck’s Hot Springs later in 1891, and continued on to Bountiful in less than a year. Centerville was reached in 1894, and Farmington in 1895. About that time, Bamberger, who was vice president and co-owner of a resort called Lake Park on the shores of the Great Salt Lake that would close in 1895 due to the lake’s receding, bought most of the original resort buildings from the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad and moved them three miles east to a swampy area in Farmington that he drained. There, he built the Lagoon Resort, which attracted riders from both Salt Lake and Ogden as well as the many towns in between.

The company was reorganized in October 1896 as the Salt Lake & Ogden Railway. The end of track remained at Lagoon from 1896 through 1902. Bamberger then resumed construction, continuing to expand his rails north, reaching Kaysville and Layton in 1906 and eventually Ogden in 1908. Passenger Service between Salt Lake City and Ogden began on August 8, 1908.

On May 28, 1910 the Salt Lake and Ogden Railway became electrified, meaning it was run by huge electric motors. The motto became “On the hour every hour.” This meant a train left Salt Lake City and Ogden each hour during the day, stopping at each city and passed each other at Kaysville, each arriving at their destination in time to make a new run on the hour. This was remarkable when it took a horse and buggy a full day to travel the same distance of 40 miles.

Though it was still the Salt Lake & Ogden Railway officially, it was locally called “the Bamberger,” and in August 1917, the name was changed officially to the Bamberger Electric Railroad. That was also the year Simon Bamberger was elected Utah’s fourth governor as the Progressive Party candidate.

Bamberger passenger and freight trains had been providing interurban railroad services to Kaysville citizens for fifteen years but during that time the city didn’t have an official depot. There were many reasons for the depot construction delay. However, when it did happen there was a citywide celebration in Kaysville.

Under the headline “WE HAVE THAT DEPOT,” a reporter wrote a story covering the dedication in The Weekly Reflex on February 3, 1921. “Kaysville has her new Bamberger Electric Railway depot and it is some depot,” the article said. “As a matter of fact, it is the finest and most commodious depot on the interurban system outside of Salt Lake City and Ogden. The building is of concrete, pressed brick, and steel and is the last word in interurban depot construction.”

Due to declining business, Bamberger Electric Railroad declared bankruptcy in 1933, emerging in 1939 as the reorganized Bamberger Railroad, dropping the word “Electric” from its name.

Things Changed Over The Next 10-15 years

The Bamberger railway survived World War II, because of a great demand for transporting goods and people. Gas rationing was prevalent and people working at Hill Field and the Naval Supply Depot needed transportation. Soon after the war its popularity began to diminish. Automobiles, trucks and buses took over. By the early 1950s, the company was struggling to make ends meet, even as it tried switching its passenger business from rail cars to buses.

In talking about the reasons for the rail line’s demise, Julian Bamberger, Simon’s son and the Bamberger president, was quoted as saying: “We hate to see this day, but it had to come. The disastrous fire last April destroyed our repair shops and service equipment. And, it seems we’re in a collision with the automobile as everyone wants to drive their car now so we have decided to switch over to highway bus operations. We will continue to serve commuters along the Salt Lake-Ogden route with buses while freight service will be handled by recently acquired diesel locomotives. Unfortunately, no one wants to ride a train anymore.”

The Bamberger ended its passenger train operations Sep. 6, 1952, and freight service ceased operations Dec. 31 1958. Much of the Bamberger right-of-way was eventually purchased by the federal government for the I-15 freeway.

Bamberger 405 Kaysville April 1943. Kaysville Elementary on the right & Station on the left.

Bamberger passenger train southbound along 100 East at junction of 100 South

The last passenger train to run between Ogden and Salt Lake City was in 1952. Kaysville Elementary School is in the background.

Southbound Freight hauling Army trucks for the War effort

The Lagoon Connection

In 1895, Simon Bamberger bought most of the original Lake Park resort buildings and moved them three miles east to a swampy area in Farmington that he drained. This was the beginning of the Lagoon Resort, which attracted riders from both Salt Lake and Ogden as well as the many towns in between.

Lagoon, has grown consistently with the population of Utah. As far back as 1908 there were 250,000 paid admissions to the park in just that one year.

Extra cars and runs to service Lagoon were added during the summer months. Admission to Lagoon was free to Bamberger passengers.

The Davis High School Connection

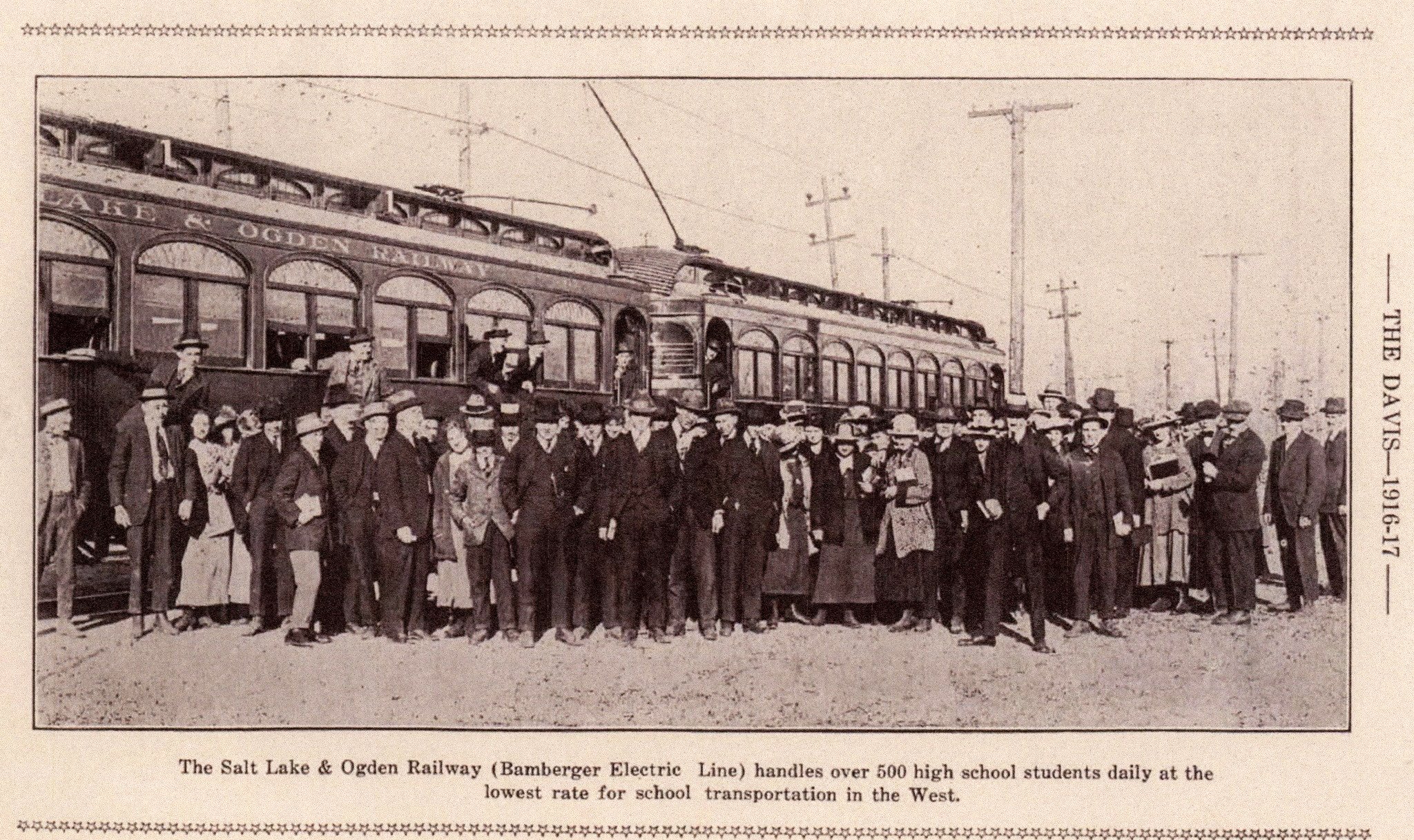

For thirty-eight years the Davis High students living in the northern and southern ends of the county rode a Bamberger Railroad ‘student train’ to school each day. The trains transported only students and special ticket rates were negotiated with the school district. The school district paid the Bamberger company for the number of student tickets distributed at the school by the teachers. The students rode free.

The extra 9 to 12 cars needed to transport students to Davis were left on the siding near the Kaysville station during school hours.

This picture shows the students getting off the train at the school. Notice the accepted student dress of the period. Boys in suits, vests, and ties and girls in long coats and dresses.

Sources

- UtahRails.net website.

- “A History of the Bamberger Railroad”, Kaysville-Layton Historical Society, 1990.

- “We Have That Depot”, Our Kaysville Story Facebook post by Bill Sanders, December 15, 2023.

- “Death of the Bamberger Railroad”, Our Kaysville Story Facebook post by Bill Sanders, October 14, 2022.

- “Davis County High School”, Our Kaysville Story Facebook post by Bill Sanders, January 18, 2023.

- The Davis Journal, March 2022, Page 6-7 , By Tom Haraldson.

- Photos courtesy of: J. Willard Marriott Library Digital Collections; UtahRails.net photo collections, Don Strack; Davis High School digital yearbooks.